Key Points

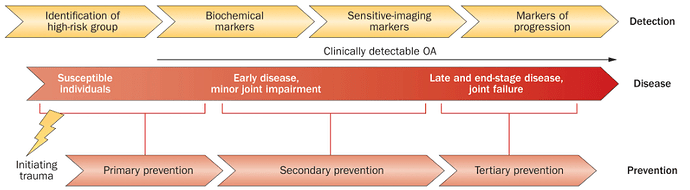

- Osteoarthritis (OA) is amenable to early prevention and treatment; not all patients with knee OA progress to severe pain or joint replacement, and patients at high risk should be identified

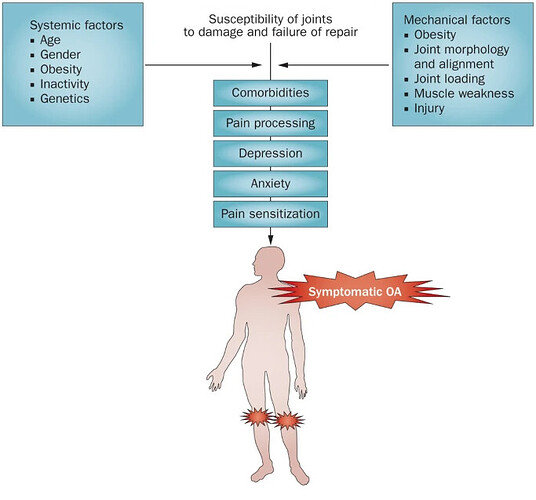

- Obesity is a major risk factor for OA, and weight loss is effective at reducing the risk of OA, but adherence to interventions is poor and should be addressed by personalized strategies

- Neuromuscular and proprioceptive training programs are successful in preventing 50% of major knee injuries during sport, which indicates that primary prevention of knee OA is possible

- Around 50% of individuals sustaining a major knee injury—with or without surgical reconstruction—develop knee OA, and secondary prevention could be valuable in patients with major knee trauma

- Impaired muscle function—a consequence of physical inactivity—is commonly seen after knee injury, is associated with knee pain, and is an independent risk factor for development of knee OA

- Biomechanical interventions, such as knee braces and exercise, show promise in altering contact stress and cartilage matrix content, suggesting ways to prevent or delay OA.

What is OA?

Osteoarthritis (OA) has been thought of as a disease of cartilage that can be effectively treated surgically at severe stages with joint arthroplasty. Today, OA is considered a whole-organ disease that is amenable to prevention and treatment at early stages. OA develops slowly over 10–15 years, interfering with activities of daily living and the ability to work. Many patients tolerate pain, and many health-care providers accept pain and disability as inevitable corollaries of OA and ageing.

Too often, health-care providers passively await final ‘joint death’, necessitating knee and hip replacements. Instead, OA should be viewed as a chronic condition, where prevention and early comprehensive-care models are the accepted norm, as is the case with other chronic diseases. Joint injury, obesity and impaired muscle function are modifiable risk factors amenable to primary and secondary prevention strategies.

The strategies that are most appropriate for each patient should be identified, by selecting interventions to correct—or at least attenuate—OA risk factors. We must also choose the interventions that are most likely to be acceptable to patients, to maximize adherence to—and persistence with—the regimes. Now is the time to begin the era of personalized prevention for knee OA.